INVESTIGACIÓN EN (JNIC2021 LIVE) - Manuel A. Serrano - Eduardo Fernández-Medina Cristina Alcaraz - Noemí de Castro - Guillermo Calvo - UCLM

←

→

Transcripción del contenido de la página

Si su navegador no muestra la página correctamente, lea el contenido de la página a continuación

EDITORES:

Manuel A. Serrano - Eduardo Fernández-Medina

Cristina Alcaraz - Noemí de Castro - Guillermo Calvo

Actas de las VI Jornadas Nacionales

(JNIC2021 LIVE)

INVESTIGACIÓN ENInvestigación en Ciberseguridad

Actas de las VI Jornadas Nacionales

( JNIC2021 LIVE)

Online 9-10 de junio de 2021

Universidad de Castilla-La ManchaInvestigación en Ciberseguridad

Actas de las VI Jornadas Nacionales

( JNIC2021 LIVE)

Online 9-10 de junio de 2021

Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

Editores:

Manuel A. Serrano,

Eduardo Fernández-Medina,

Cristina Alcaraz

Noemí de Castro

Guillermo Calvo

Cuenca, 2021© de los textos e ilustraciones: sus autores

© de la edición: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

Edita: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha.

Colección JORNADAS Y CONGRESOS n.º 34

© de los textos: sus autores.

© de la edición: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha.

© de los textos e ilustraciones: sus autores

© de la edición: Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

Edita: Ediciones Esta

de la Universidad

editorial esdemiembro

Castilla-Lade

Mancha

la UNE, lo que garantiza la difusión y

comercialización de sus publicaciones a nivel nacional e internacional

Colección JORNADAS

Edita: Ediciones de YlaCONGRESOS

Universidad de n.º Castilla-La

34 Mancha.

Colección JORNADAS Y CONGRESOS n.º 34

I.S.B.N.: 978-84-9044-463-4

Esta editorial es miembro de la UNE, lo que garantiza la difusión y comercialización de sus publi-

caciones a nivel nacional e internacional.

D.O.I.: http://doi.org/10.18239/jornadas_2021.34.00

Esta editorial es miembro de la UNE, lo que garantiza la difusión y

I.S.B.N.: 978-84-9044-463-4

comercialización de sus publicaciones a nivel

nacional e internacional

D.O.I.: http://doi.org/10.18239/jornadas_2021.34.00

I.S.B.N.:

Esta obra 978-84-9044-463-4

se encuentra bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons CC BY 4.0.

D.O.I.: http://doi.org/10.18239/jornadas_2021.34.00

Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta

Esta obra se encuentra bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons CC BY 4.0.

obra no incluida en la licencia Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 solo puede ser realizada con la

Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra no incluida

autorización

en expresa

la licencia Creative de los CC

Commons titulares, salvopuede

BY 4.0 solo excepción prevista

ser realizada con la por la ley. Puede

autorización Vd.

expresa de losacceder

titulares, al

texto completo de la licencia en este enlace:

salvo excepción prevista por la ley. Puede Vd. acceder al texto completo de la licencia en este enlace: https://

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.es

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.es

Esta obra se encuentra bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons CC BY 4.0.

Hecho en España (U.E.) – Made in Spain (E.U.)

Hecho en España

Cualquier forma de(U.E.) – Made indistribución,

reproducción, Spain (E.U.)comunicación pública o transformación de esta

obra no incluida en la licencia Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 solo puede ser realizada con la

autorización expresa de los titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la ley. Puede Vd. acceder al

texto completo de la licencia en este enlace:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.es

Hecho en España (U.E.) – Made in Spain (E.U.)Bienvenida del Comité Organizador

Tras la parada provocada por la pandemia en 2020, las VI Jornadas Nacionales de Investiga-

ción en Ciberseguridad ( JNIC) vuelven el 9 y 10 de Junio del 2021 con energías renovadas, y por

primera vez en su historia, en un formato 100% online. Esta edición de las JNIC es organizada

por los grupos GSyA y Alarcos de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha en Ciudad Real, y

con la activa colaboración del comité ejecutivo, de los presidentes de los distintos comités de

programa y del Instituto Nacional de Ciberseguridad (INCIBE). Continúa de este modo la

senda de consolidación de unas jornadas que se celebraron por primera vez en León en 2015 y

le siguieron Granada, Madrid, San Sebastián y Cáceres, consecutivamente hasta 2019, y que,

en condiciones normales se habrían celebrado en Ciudad Real en 2020.

Estas jornadas se han convertido en un foro de encuentro de los actores más relevantes en

el ámbito de la ciberseguridad en España. En ellas, no sólo se presentan algunos de los trabajos

científicos punteros en las diversas áreas de ciberseguridad, sino que se presta especial atención

a la formación e innovación educativa en materia de ciberseguridad, y también a la conexión

con la industria, a través de propuestas de transferencia de tecnología. Tanto es así que, este año

se presentan en el Programa de Transferencia algunas modificaciones sobre su funcionamiento

y desarrollo que han sido diseñadas con la intención de mejorarlo y hacerlo más valioso para

toda la comunidad investigadora en ciberseguridad.

Además de lo anterior, en las JNIC estarán presentes excepcionales ponentes (Soledad

Antelada, del Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Ramsés Gallego, de Micro Focus y

Mónica Mateos, del Mando Conjunto de Ciberdefensa) mediante tres charlas invitadas y se

desarrollarán dos mesas redondas. Éstas contarán con la participación de las organizaciones

más relevantes en el panorama industrial, social y de emprendimiento en relación con la ciber-

seguridad, analizando y debatiendo el papel que está tomando la ciberseguridad en distintos

ámbitos relevantes.

En esta edición de JNIC se han establecido tres modalidades de contribuciones de inves-

tigación, los clásicos artículos largos de investigación original, los artículos cortos con investi-

gación en un estado más preliminar, y resúmenes extendidos de publicaciones muy relevantes

y de alto impacto en materia de ciberseguridad publicados entre los años 2019 y 2021. En el

caso de contribuciones de formación e innovación educativa, y también de transferencias se

han considerado solamente artículos largos. Se han recibido para su valoración un total de 86

7Bienvenida del Comité Organizador

contribuciones organizadas en 26, 27 y 33 artículos largos, cortos y resúmenes ya publicados,

de los que los respectivos comités de programa han aceptado 21, 19 y 27, respectivamente. En

total se ha contado con una ratio de aceptación del 77%. Estas cifras indican una participación

en las jornadas que continúa creciendo, y una madurez del sector español de la ciberseguridad

que ya cuenta con un volumen importante de publicaciones de alto impacto.

El formato online de esta edición de las jornadas nos ha motivado a organizar las jornadas

de modo más compacto, distinguiendo por primera vez entre actividades plenarias (charlas

invitadas, mesas redondas, sesión de formación e innovación educativa, sesión de transfe-

rencia de tecnología, junto a inauguración y clausura) y sesiones paralelas de presentación de

artículos científicos. En concreto, se han organizado 10 sesiones de presentación de artículos

científicos en dos líneas paralelas, sobre las siguientes temáticas: detección de intrusos y gestión

de anomalías (I y II), ciberataques e inteligencia de amenazas, análisis forense y cibercrimen,

ciberseguridad industrial, inteligencia artificial y ciberseguridad, gobierno y riesgo, tecnologías

emergentes y entrenamiento, criptografía, y finalmente privacidad.

En esta edición de las jornadas se han organizado dos números especiales de revistas con

elevado factor de impacto para que los artículos científicos mejor valorados por el comité de

programa científico puedan enviar versiones extendidas de dichos artículos. Adicionalmente, se

han otorgado premios al mejor artículo en cada una de las categorías. En el marco de las JNIC

también hemos contado con la participación de la Red de Excelencia Nacional de Investigación

en Ciberseguridad (RENIC), impulsando la ciberseguridad a través de la entrega de los premios

al Mejor Trabajo Fin de Máster en Ciberseguridad y a la Mejor Tesis Doctoral en Ciberseguridad. Tam-

bién se ha querido acercar a los jóvenes talentos en ciberseguridad a las JNIC, a través de un CTF

(Capture The Flag) organizado por la Universidad de Extremadura y patrocinado por Viewnext.

Desde el equipo que hemos organizado las JNIC2021 queremos agradecer a todas aquellas

personas y entidades que han hecho posible su celebración, comenzando por los autores de

los distintos trabajos enviados y los asistentes a las jornadas, los tres ponentes invitados, las

personas y organizaciones que han participado en las dos mesas redondas, los integrantes de

los distintos comités de programa por sus interesantes comentarios en los procesos de revisión

y por su colaboración durante las fases de discusión y debate interno, los presidentes de las

sesiones, la Universidad de Extremadura por organizar el CTF y la empresa Viewnext por

patrocinarlo, los técnicos del área TIC de la UCLM por el apoyo con la plataforma de comu-

nicación, los voluntarios de la UCLM y al resto de organizaciones y entidades patrocinadoras,

entre las que se encuentra la Escuela Superior de Informática, el Departamento de Tecnologías

y Sistemas de Información y el Instituto de Tecnologías y Sistemas de Información, todos ellos

de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, la red RENIC, las cátedras (Telefónica e Indra)

y aulas (Avanttic y Alpinia) de la Escuela Superior de Informática, la empresa Cojali, y muy

especialmente por su apoyo y contribución al propio INCIBE.

Manuel A. Serrano, Eduardo Fernández-Medina

Presidentes del Comité Organizador

Cristina Alcaraz

Presidenta del Comité de Programa Científico

Noemí de Castro

Presidenta del Comité de Programa de Formación e Innovación Educativa

Guillermo Calvo Flores

Presidente del Comité de Transferencia Tecnológica

8Índice General

Comité Ejecutivo.............................................................................................. 11

Comité Organizador........................................................................................ 12

Comité de Programa Científico....................................................................... 13

Comité de Programa de Formación e Innovación Educativa........................... 15

Comité de Transferencia Tecnológica............................................................... 17

Comunicaciones

Sesión de Investigación A1: Detección de intrusiones y gestión de anomalías I 21

Sesión de Investigación A2: Detección de intrusiones y gestión de anomalías II 55

Sesión de Investigación A3: Ciberataques e inteligencia de amenazas............. 91

Sesión de Investigación A4: Análisis forense y cibercrimen............................. 107

Sesión de Investigación A5: Ciberseguridad industrial y aplicaciones.............. 133

Sesión de Investigación B1: Inteligencia Artificial en ciberseguridad............... 157

Sesión de Investigación B2: Gobierno y gestión de riesgos.............................. 187

Sesión de Investigación B3: Tecnologías emergentes y entrenamiento en

ciberseguridad................................................................................................... 215

Sesión de Investigación B4: Criptografía.......................................................... 235

Sesión de Investigación B5: Privacidad............................................................. 263

Sesión de Transferencia Tecnológica................................................................ 291

Sesión de Formación e Innovación Educativa.................................................. 301

Premios RENIC.............................................................................................. 343

Patrocinadores................................................................................................. 349

9Comité Ejecutivo

Juan Díez González INCIBE

Luis Javier García Villalba Universidad de Complutense de Madrid

Eduardo Fernández-Medina Patón Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

Guillermo Suárez-Tangil IMDEA Networks Institute

Andrés Caro Lindo Universidad de Extremadura

Pedro García Teodoro Universidad de Granada. Representante

de red RENIC

Noemí de Castro García Universidad de León

Rafael María Estepa Alonso Universidad de Sevilla

Pedro Peris López Universidad Carlos III de Madrid

11Comité Organizador

Presidentes del Comité Organizador

Eduardo Fernández-Medina Patón Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

Manuel Ángel Serrano Martín Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

Finanzas

David García Rosado Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

Luis Enrique Sánchez Crespo Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

Actas

Antonio Santos-Olmo Parra Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

Difusión

Julio Moreno García-Nieto Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

José Antonio Cruz Lemus Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

María A Moraga de la Rubia Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

Webmaster

Aurelio José Horneros Cano Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

Logística y Organización

Ignacio García-Rodriguez de Guzmán Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

Ismael Caballero Muñoz-Reja Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

Gregoria Romero Grande Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

Natalia Sanchez Pinilla Universidad de Castilla-la Mancha

12Comité de Programa Científico

Presidenta

Cristina Alcaraz Tello Universidad de Málaga

Miembros

Aitana Alonso Nogueira INCIBE

Marcos Arjona Fernández ElevenPaths

Ana Ayerbe Fernández-Cuesta Tecnalia

Marta Beltrán Pardo Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

Carlos Blanco Bueno Universidad de Cantabria

Jorge Blasco Alís Royal Holloway, University of London

Pino Caballero-Gil Universidad de La Laguna

Andrés Caro Lindo Universidad de Extremadura

Jordi Castellà Roca Universitat Rovira i Virgili

José M. de Fuentes García-Romero

de Tejada Universidad Carlos III de Madrid

Jesús Esteban Díaz Verdejo Universidad de Granada

Josep Lluis Ferrer Gomila Universitat de les Illes Balears

Dario Fiore IMDEA Software Institute

David García Rosado Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

Pedro García Teodoro Universidad de Granada

Luis Javier García Villalba Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Iñaki Garitano Garitano Mondragon Unibertsitatea

Félix Gómez Mármol Universidad de Murcia

Lorena González Manzano Universidad Carlos III de Madrid

María Isabel González Vasco Universidad Rey Juan Carlos I

Julio César Hernández Castro University of Kent

Luis Hernández Encinas CSIC

Jorge López Hernández-Ardieta Banco Santander

Javier López Muñoz Universidad de Málaga

Rafael Martínez Gasca Universidad de Sevilla

Gregorio Martínez Pérez Universidad de Murcia

13David Megías Jiménez Universitat Oberta de Cataluña

Luis Panizo Alonso Universidad de León

Fernando Pérez González Universidad de Vigo

Aljosa Pasic ATOS

Ricardo J. Rodríguez Universidad de Zaragoza

Fernando Román Muñoz Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Luis Enrique Sánchez Crespo Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha

José Soler Technical University of Denmark-DTU

Miguel Soriano Ibáñez Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña

Victor A. Villagrá González Universidad Politécnica de Madrid

Urko Zurutuza Ortega Mondragon Unibertsitatea

Lilian Adkinson Orellana Gradiant

Juan Hernández Serrano Universitat Politécnica de Cataluña

14Comité de Programa de Formación e Innovación Educativa

Presidenta

Noemí De Castro García Universidad de León

Miembros

Adriana Suárez Corona Universidad de León

Raquel Poy Castro Universidad de León

José Carlos Sancho Núñez Universidad de Extremadura

Isaac Agudo Ruiz Universidad de Málaga

Ana Isabel González-Tablas Ferreres Universidad Carlos III de Madrid

Xavier Larriva Universidad Politécnica de Madrid

Ana Lucila Sandoval Orozco Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Lorena González Manzano Universidad Carlos III de Madrid

María Isabel González Vasco Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

David García Rosado Universidad de Castilla - La Mancha

Sara García Bécares INCIBE

15Comité de Transferencia Tecnológica

Presidente

Guillermo Calvo Flores INCIBE

Miembros

José Luis González Sánchez COMPUTAEX

Marcos Arjona Fernández ElevenPaths

Victor Villagrá González Universidad Politécnica de Madrid

Luis Enrique Sánchez Crespo Universidad de Castilla – La Mancha

17Sesión de Investigación B4: Criptografía

http://doi.org/10.18239/jornadas_2021.34.54

Homomorphic SVM Inference for Fraud Detection

A. Vázquez-Saavedra ID , G. Jiménez-Balsa ID , J. Loureiro-Acuña ID M. Fernández-Veiga ID , A. Pedrouzo-Ulloa ID

Gradiant atlanTTic Research Center, Universidade de Vigo

Carretera de Vilar, 56, Vigo, Pontevedra, 36214, Spain E.E. Telecomunicación, Vigo 36310, Spain

{avsaavedra, gjimenez, jloureiro}@gradiant.org mveiga@det.uvigo.es, apedrouzo@gts.uvigo.es

Abstract—Nowadays, cloud computing has become a very medical data, religious information, etc. This type of data

promising solution for almost all companies, as it offers the pos- is protected by law and, as companies could be exposed to

sibility of saving costs by outsourcing computation on-demand. different sanctions, they are forced to guarantee a certain

However, some companies deal with private information, which

must be protected before outsourcing. Banks, whose financial level of protection. Even so, although conventional crypto-

information is highly sensitive, are one remarkable example of graphic techniques allow for secure storage in the cloud,

this problem. Their typical processes must be run on their data protection is not so easy if some sort of computation

systems for security and regulation reasons, which impedes has to be applied on the data. Thus, in view of all these

to take advantage of the scalability and flexibility benefits shortcomings, companies which handle sensitive data should

introduced by the cloud. A relevant example on which we

focus in this work is the case of fraud detection systems, for seemingly avoid cloud-based solutions.

which we propose the use of modern lattice-based homomorphic Precisely, the field of privacy-preserving machine learning

encryption for its secure execution. To this end, we implement (PPML) [1] deals with the different security and privacy

and validate the performance of a homomorphic SVM (Support threats appearing in machine learning (ML). Actually, paying

Vector Machine) classifier for secure fraud detection, showing

attention to the scenario of cloud computing, and among

the feasibility of securely outsourcing fraud detection inference.

the broad set of available tools inside PPML, homomorphic

Index Terms—Support Vector Machines, Fraud Detection, encryption techniques, which enable secure processing on

Homomorphic Encryption, Lattice-based Cryptography encrypted data, seem to be a perfect fit for secure outsourcing.

Type of contribution: Ongoing research

A. Our Contributions

I. I NTRODUCTION

The impact of cloud computing on industry and also end Our scenario is set inside a banking fraud context [2], on

users is difficult to estimate: many aspects of everyday life which banks make use of fraud detection systems that require

have been transformed by the omnipresence of software run- a large amount of resources to operate. Bank transactions do

ning on cloud networks. On the one hand, cloud computing al- not follow a uniform time distribution, so a good solution

lows companies to optimise costs and increase their offerings, for banks is to outsource their fraud detection systems, which

without having the need of purchasing and managing all the allows them to take advantage of the flexibility and scalability

hardware and software. This allows them to launch globally- provided by the cloud.

available apps and online services without having to spend Our main contribution is to implement and showcase the

resources on the platform on which they will run. On the other feasibility of a solution based on homomorphic cryptography

hand, end users can access these applications immediately (see Section II), which enables to securely outsource the

and without any specific requirements, as all these services fraud detection systems. In particular, we have implemented

are easily available on the Internet. Unfortunately, not all a SVM (Support Vector Machine) inference algorithm in the

companies can benefit from the cloud computing approach. encrypted domain (see Sections III and IV); being this classi-

A major disadvantage which is present in cloud-based fier tailored for bank fraud detection. Our homomorphic SVM

applications is their underlying security. Actually, the use of classifier allows a bank to make secure encrypted predictions

cloud-based services always leads to the storage of informa- in an untrusted environment.

tion in third party systems, which could be often considered In order to test its feasibility: (1) we have designed a proof

as untrusted environments. Although, in general, this is not a of concept based on a client-server model (see Section IV)

problem for many applications, the situation is considerably and, (2) we have evaluated the runtime and classification

aggravated in those use cases which deal with especially performance of the system (see Section V).

privacy-sensitive information, on which security is a priority Notation and Structure: We represent vectors and matrices

and must be maximised. by boldface lowercase and uppercase letters, respectively.

The list of related use cases encompasses companies that Polynomials are denoted with regular lowercase letters, ignor-

must handle sensitive information, such as financial and ing the polynomial variable (e.g., a instead of a(z)). Finally,

the Hadamard product of two vectors is a ◦ b.

This work was funded by the Ayudas Cervera para Centros Tecnológicos, The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section II

grant of the Spanish Centre for the Development of Industrial Technology briefly reviews the used homomorphic encryption scheme.

(CDTI) under the project EGIDA (CER-20191012). Also funded by the Agen- Section III details the bank fraud detection scenario, the

cia Estatal de Investigación (Spain) and the European Regional Development

Fund (ERDF) under project RODIN (PID2019-105717RB-C21), and by the dataset and the SVM classifier. Section IV introduces the

Xunta de Galicia and ERDF under project ED431G2019/08. design of our system and the homomorphic classifier. Finally,

245Sesión de Investigación B4: Criptografía

TABLE I

H IGH LEVEL DESCRIPTION OF THE CKKS SCHEME [9] banks could outsource this information securely and take

Parameters: Let Rq [z] be the quotient polynomial ring Zq [z]/(1 + z n ). Then, ciphertexts from the advantage of the benefits provided by the cloud.

ECKKS scheme are composed of two polynomial elements from Rq [z], and plaintexts belong to the

set CP such that P = n/2. Finally, q and n (for simplicity we omit some internal parameters) are

chosen in terms of the security parameter λ. A. Dataset

Input: Security parameter λ

ECKKS .SecKeyGen

Output: Secret key sk The dataset used for this paper is called IEEE-CIS Fraud

ECKKS .PubKeyGen

Input: Secret key sk

Output: Public key pk, evaluation key evk and rotation key rtk

Detection [10]. It is composed of real-world e-commerce

ECKKS .Enc

Input: Plaintext m ∈ CP transactions provided by Vesta, a leader payment service com-

Output: A ciphertext c = (c0 , c1 ) ∈ Rq2 [z]

Input: A ciphertext c = (c 0 , c 1 ) ∈ Rq2 [z] encrypting a plaintext m ∈ CP

pany. The dataset is divided into 4 files train transaction.csv,

ECKKS .Dec

Output: A plaintext m ∈ CP train identity.csv, test transaction.csv and test identity.csv.

Input: Ciphertexts c and c encrypting, respectively, m and m

ECKKS .Add Output: A ciphertext c = (c 2

0 , c1 ) ∈ Rq [z] encrypting m + m = m ∈

However, we only use the files train transaction.csv and

CP train identity.csv, as the other two are unlabeled and we could

Input: A plaintext m ∈ CP and a ciphertext c encrypting m

ECKKS .LinHadMult Output: A ciphertext c = (c 2

0 , c1 ) ∈ Rq [z] encrypting m ◦ m = m ∈

not use the samples they contain to test the results of the

CP

Input: Evaluation key evk, and ciphertexts c and c encrypting, respectively,

inference. Consequently, these two training files are combined,

ECKKS .HadMult

m and m finally obtaining a dataset with 590540 rows and 434 features.

Output: A ciphertext c = (c

0 , c1 ) ∈ Rq [z] encrypting m ◦ m = m ∈

2

CP

Input: A ciphertext c encrypting m ∈ CP B. Dataset pre-processing

ECKKS .Rot Output: A ciphertext c = (c 0 , c 1 ) ∈ Rq2 [z] encrypting m ∈ CP , which is

the result of applying a rotation over the components of m Given the large dimensionality of the training dataset, an

adequate pre-processing is required before training. As our

Section V evaluates the performance of our system, and main objective in this work focuses on implementing the SVM

Section VI discusses some future work lines. inference function in the encrypted domain, we have followed

the guidelines for data pre-processing and feature selection

II. P RELIMINARIES : H OMOMORPHIC E NCRYPTION

proposed in [10]. According to their recommendations:

Homomorphic encryption appears as a very promising tool • The number of features is reduced from 434 to 115.

for secure processing [3]. One relevant example is the Paillier • The columns with missing values are filled with the

cryptosystem [4], which has been used in a broad range of mean, mode or the most frequent category among the

different applications [5]. It presents a group homomorphism present values in the corresponding column.

which enables additions between two encrypted values, and

multiplications between a ciphertext and a plaintext. C. SVM linear kernel

Consequently, Paillier could be a perfect candidate to We have chosen a Support Vector Machine (SVM) clas-

implement our proposed encrypted detector for bank fraud sifier due to its good performance for the fraud detection

detection. However, modern lattice-based cryptosystems out- scenario [10]. SVMs correspond to a type of binary classifiers

perform Paillier in several aspects: (1) more complex applica- which, given a set of training samples, maximize the gap

tions are possible as they present a ring homomorphism which between the two considered groups (e.g., 1 fraud vs −1 non-

enables multiplication between two ciphertexts (e.g., the train- fraud in our scenario).

ing of a SVM [6]), and (2) better performance, as Paillier is Specifically, in this work we are interested in the expression

slower even when considering only linear operations [7], [8]. of the SVM classifier:

In view of the above points, we make use of the CKKS

scheme [9], which is a lattice-based cryptosystem especially

L

adapted to work with approximate arithmetic operations.

sign yi αi K(xi , x) + b, (1)

i=1

A. A concrete homomorphic encryption scheme

score

We give a brief description of the CKKS scheme ECKKS in

Table I. It is defined as a conventional public-key encryption where x is the input sample, and the rest of parameters are

scheme E = {SecKeyGen, PubKeyGen, Enc, Dec}, but ex- obtained through the SVM training: b is the bias, αi are the

tended with Add, HadMult, LinHadMult and Rot procedures. dual coefficients, and xi and yi are, respectively, the support

For further details of the scheme we refer the reader to [9]. vectors together with their associated label (1 or −1). We refer

to [11] for more details on the training of SVMs.

III. U SE CASE However, due to the limitations of homomorphic encryption

Banks use fraud detection systems that require a large schemes, two additional points must be considered:

amount of computational resources. This results in significant • The sign(·) function can be very costly to be homomor-

costs for banks to keep their systems up and running. One phically computed. As it does not introduce a relevant

possible approach for banks is to outsource these systems to overhead, we have moved it to the client side, which

the cloud where, in addition to saving costs, they would obtain calculates it after decryption.

more flexible systems. • Among the possible choices for the kernel K(·, ·) func-

However, banking information is sensitive and traditional tion, we make use of a linear kernel K(u, v) = u · v;

techniques only allow to work with data in clear, what can be a mainly due to its simplicity and good behaviour for

security problem. Consequently, we propose to implement the the fraud detection problem [10]. Additionally, it brings

evaluation phase of an important machine learning algorithm about an important efficiency advantage thanks to the fact

such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) in the encrypted that the inner product is distributive over vector addition,

domain. Therefore, by directly working with encrypted data, which enables to considerably simplify the classifier.

246Sesión de Investigación B4: Criptografía

Consequently, taking into account the above changes, our Microsoft Seal [12] and Lattigo [13] libraries. For running the

homomorphic classifier turns out to be: homomorphic inference, the following steps must be followed:

1) The Client authenticates to the server

score = yi αi xi ·

x + b. (2) 2) The Client creates a key pair and sends its public part

i input sample to the server

linear SVM model

3) The Client packs and encrypts the data samples that

wants to infer and sends them to the server

For more details on its homomorphic computation and the dif- 4) The Server retrieves the SVM model and public keys

ferent packing methods, we refer the reader to Section IV-B. from database

IV. SVM H OMOMORPHIC I NFERENCE 5) The Server does the Homomorphic SVM Inference and

sends the result to the client

So as to showcase the potential and practicability of homo- 6) The Client decrypts the result and shows it to the user

morphic encryption for PPML, and more specifically, for the

encrypted execution of SVM inference, we have implemented B. Data packing

a client-server prototype. Starting from the use case, bank As the CKKS scheme [9] allows for homomorphic approx-

fraud detection with a SVM, the needed homomorphic oper- imate additions and Hadamard products between encrypted

ations for both encryption/decryption and for the encrypted vectors (see Section II), finding the best way of packing

inference using a linear kernel have been implemented. the data before encryption is fundamental to optimize the

performance of our encrypted SVM classifier.

A. Design

With this aim, we have explored two different packing

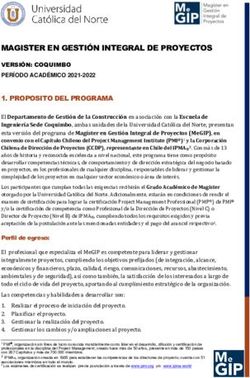

The design of the prototype follows a client-server approach methods [2], which we denote in this work as column packing

to emulate the client and cloud side for an scenario of and flattened packing respectively. Let X be a matrix of size

outsourced computation in an untrusted environment. The N × M where N represents the number of input samples

client is responsible of encryption and decryption, so the input we want to query for detection, and M corresponds to the

data is protected from the moment it leaves the client. The number of features for each input sample. We also assume

server is responsible of processing the encrypted data, and of that the instantiated CKKS scheme has a packing capacity of

finally sending back to the client the encrypted result. Figure 1 P complex slots. We briefly describe these two methods next:

depicts the main components of the secure SVM prototype. • Column packing: It encodes the columns of X separately

in different ciphertexts. This packing naturally fits into

the SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) paradigm,

which makes it convenient for those cases where the

number of input samples N in the client query is large.

• Flattened packing: We represent the matrix X as

a reshape on which all the rows are concatenated

into a “flattened” vector of length N · M such as

[row1 (X), . . . , rowN (X)]. Then, we encrypt all the rowi

blocks using the minimal possible number of ciphertexts,

i.e., each ciphertext has

M

P

different rows from X.

Contrarily to the former, the use of a flattened packing

optimizes the storage in those cases on which N is small

in relation to the ciphertext packing capacity P .

Homomorphic inference: Regarding the concrete algorithms

Fig. 1. System architecture in the encrypted domain, there are also some important

As shown in Figure 1, the prototype is composed of two differences for each packing:

different clients (one is web based and the other one command • Inference with column packing: It follows the same

line based) and one server. All 3 components make use of structure as its counterpart in clear. We homomorphically

a database and of a cryptographic library that implements compute Eq. (2) by means of both ECKKS .LinHadMult

the needed cryptographic primitives for each component. The and ECKKS .Add primitives. It is worth noting that, as a

clients database stores the user homomorphic cryptographic different score is calculated by default in parallel for P

keys and the transactions data samples that are classified complex slots, we directly obtain the inference for P

with the Homomorphic SVM Inference. The server database different input samples in each output ciphertext.

stores users authentication details, users public homomorphic • Inference with flattened packing: It requires a more cum-

cryptographic keys and parameters, and the SVM model. The bersome algorithm on which not only ECKKS .LinHadMult

clients cryptographic library implements the generation of and ECKKS .Add primitives are needed, but also

cryptographic keys and parameters, and also the data pack- ECKKS .Rot must be applied to relocate the partial results

ing/unpacking and encryption/decryption primitives, while the of the inner product. In this case each output ciphertext

server cryptographic library implements the encrypted kernel contains

MP

different score values.

evaluation primitives. In order to implement the primitives for Tables II and III include a summary of the existing trade-

encrypted processing, the cryptographic libraries make use of offs between both packing methods. Note that the flattened

247Sesión de Investigación B4: Criptografía

TABLE II

C OMPUTATIONAL COST FOR EACH PACKING METHOD VI. C ONCLUSIONS AND F UTURE W ORK

Method Ciphertext operations This work shows that homomorphic encryption is a key

Column packing NP

(M mult. + M add.) enabler technology for migrating highly sensitive process to

Flattened packing N

P

(1 mult. + log2 M

add. + log2 M

rot.) the cloud. Our proof of concept prototype demonstrates the

M

feasibility of running the fraud detection inference in the un-

TABLE III trusted domain, while maintaining the prediction performance

S TORAGE REQUIREMENTS FOR EACH PACKING METHOD and also with a feasible execution performance. As future

Method # of ciphertexts

work, we envision several extensions for our prototype:

Column packing M N

• A more complete comparison considering other alter-

NP

Flattened packing P

native cryptographic schemes/techniques as Paillier [4],

M

BFV [14], and functional encryption [15]

• Deploy the server in a real cloud environment in order

packing also requires to generate the rotation key matrices to measure the instantiation costs in a realistic scenario.

rtk which are used for the homomorphic slot rotations. • Protect the model in the execution environment. This

corresponds to the case on which the server infrastructure

V. I MPLEMENTATION R ESULTS provider and the model owner are not the same entity.

• Extend the prototype considering more complex kernels;

In this section we show the results obtained in our imple-

e.g., polynomial and RBF (Radial Basis Function).

mentation. All the experiments were conducted using a test-

• The implementation in the untrusted domain of the

bed composed of a physical device with a CPU i7-4710HQ,

sign(·) function. Currently, there exist mechanisms for its

12GB of RAM and Ubuntu Desktop 20.04.

homomorphic approximation with CKKS [16]. Note this

In the first place, we evaluate the quality of the inference of

adds an additional degree of protection to the model, as

our implementation against the inference in the clear. These

it is harder for the client reverse engineering the model.

results are shown in Table IV. In order to test the classification

performance, we have considered three different metrics: R EFERENCES

• Accuracy: % of correct predictions. [1] M. Al-Rubaie and J. M. Chang, “Privacy-preserving machine learning:

• Precision: % of correctly detected positives among all Threats and solutions,” IEEE Secur. Priv., vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 49–58,

2019.

detected positives. [2] A. Vázquez-Saavedra, “Study and applications of homomorphic

• Recall: % of correctly detected positives among all encryption algorithms to privacy preserving svm inference for a

positives. bank fraud detection context,” Master’s thesis, Telecommunication

Engineering School, University of Vigo, 2021. [Online]. Available:

http://castor.det.uvigo.es:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/533

TABLE IV

[3] Homomorphic encryption standardization. [Online]. Available: https:

I NFERENCE RESULTS : M ACHINE L EARNING CONTEXT

//homomorphicencryption.org/

Library Packing Accuracy Precision Recall [4] P. Paillier, “Public-key cryptosystems based on composite degree resid-

Plain - 96.6% 5.44% 46.8% uosity classes,” in EUROCRYPT, ser. LNCS, vol. 1592. Springer, 1999,

SEAL Flattened 96.4% 4.39% 32.5% pp. 223–238.

SEAL Column 96.6% 3.72% 70.4% [5] R. L. Lagendijk, Z. Erkin, and M. Barni, “Encrypted signal processing

Lattigo Flattened 96.6% 3.72% 70.4% for privacy protection: Conveying the utility of homomorphic encryption

Lattigo Column 96.6% 3.72% 70.4% and multiparty computation,” IEEE Signal Process. Mag., vol. 30, no. 1,

pp. 82–105, 2013.

[6] S. Park, J. Byun, J. Lee, J. H. Cheon, and J. Lee, “He-friendly algorithm

TABLE V for privacy-preserving SVM training,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 57 414–

I NFERENCE RESULTS : PERFORMANCE CONTEXT 57 425, 2020.

(N = 147635, M = 114, P = 4096) [7] A. Pedrouzo-Ulloa, J. R. Troncoso-Pastoriza, and F. Pérez-González,

Library Packing PS time (ms) PC time (ms) Size (KB) “Number theoretic transforms for secure signal processing,” IEEE

SEAL Flattened 4.03 3.66 31.3 Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur., vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 1125–1140, 2017.

SEAL Column 0.12 1.69 14.0 [8] J. R. Troncoso-Pastoriza, A. Pedrouzo-Ulloa, and F. Pérez-González,

Lattigo Flattened 2.34 16.8 41.9 “Secure genomic susceptibility testing based on lattice encryption,” in

Lattigo Column 0.03 8.29 18.7 IEEE ICASSP. IEEE, 2017, pp. 2067–2071.

[9] J. H. Cheon, A. Kim, M. Kim, and Y. S. Song, “Homomorphic

encryption for arithmetic of approximate numbers,” in ASIACRYPT, ser.

Another important aspect that we have assessed is the LNCS, vol. 10624. Springer, 2017, pp. 409–437.

runtime performance. In this case, Table V includes: [10] Z. Wu. (2020) Kaggle — IEEE Fraud Detection (EDA). [Online].

Available: https://blog.csdn.net/Tinky2013/article/details/104215953

• Server (PS ) runtime: the required time to perform the [11] I. Steinwart and A. Christmann, “Support vector machines,” in Infor-

inference function in the server. mation science and statistics, 2008.

[12] “Microsoft SEAL (release 3.0),” http://sealcrypto.org, Oct. 2018, mi-

• Client (PC ) runtime: total time taken by the client to crosoft Research, Redmond, WA.

encode/decode + encrypt/decrypt the different samples. [13] C. Mouchet, J.-P. Bossuat, J. Troncoso-Pastoriza, and J. Hubaux,

• Size: size of the information sent from client to server. “Lattigo: a multiparty homomorphic encryption library in go,” 2020.

[14] J. Fan and F. Vercauteren, “Somewhat practical fully homomorphic

Note that our results consider the execution of several encryption,” IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch., vol. 2012, p. 144, 2012.

inferences in parallel, so the included runtimes are normalized [15] T. Marc, M. Stopar, J. Hartman, M. Bizjak, and J. Modic, “Privacy-

enhanced machine learning with functional encryption,” in ESORICS,

to measure the estimated runtime for a single inference of each ser. LNCS, vol. 11735. Springer, 2019, pp. 3–21.

type of packing. As the transmission times have not been taken [16] E. Lee, J. Lee, J. No, and Y. Kim, “Minimax approximation of sign

into account, we include the size of transmitted information function by composite polynomial for homomorphic comparison,” IACR

Cryptol. ePrint Arch., vol. 2020, p. 834, 2020.

per inference.

248También puede leer